Retired HFC instructor’s memoir accepted into Museum of Peace Corps Experience and Library of Michigan

Retired HFC English instructor Ed Demerly’s memoir about his time in the Peace Corps during the late 1960s has recently been included into the Museum of the Peace Corps Experience in Washington, D.C. and the Library of Michigan in Lansing for its historical value.

“Now that the book has been out and I’m getting replies, it’s heartening for me to recognize that some people who buy it are interested in what Peace Corps service was like back then,” said Demerly. “Today, there are nearly 100 countries where Peace Corps workers serve.”

Demerly – who also recently won the College English Association's most precious award, the Fred L. Standley CEA Lifetime Achievement Award – lives in Bloomfield Hills with Martha, his wife of 40 years. They have two children and four grandchildren.

“On a more personal note, I’m sure that living in Asia during my time in the Peace Corps influenced my decision to adopt a 5-year-old Korean daughter in 1975,” he said.

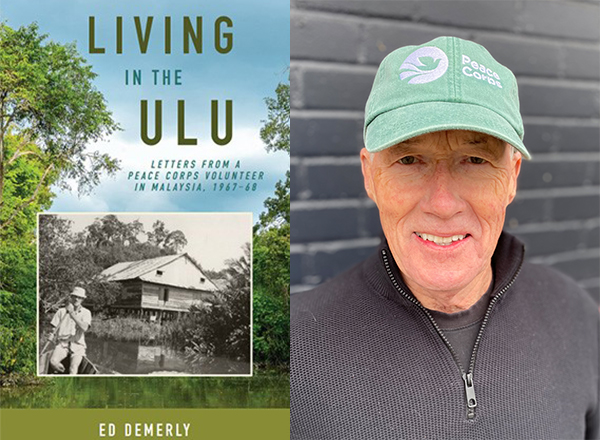

Demerly is the author of Living in the Ulu: Letters from a Peace Corps Volunteer in Malaysia, 1967-68 (Mission Point Press). This is his second memoir, following First Years: A Farm Boy Faces the Future.

“My publisher suggested that I donate my first memoir to the Library of Michigan for its focus on rural Michigan in the mid-20th century,” explained Demerly. “They deemed it worthy of meeting their standards for acceptance. Thus, when the second memoir was published, I offered to donate a copy, even though the content was not centered on Michigan. Again, because I grew up in Michigan and spent most of my adult life working in Michigan, and because the content reflected the challenges a Michigander faced living on the other side of the world writing to his Michigan farm parents, they also accepted Living in the Ulu for inclusion.”

“Ed Demerly‘s writing is richly detailed and deeply felt”

MPCE it is a partnership with the Peace Corps Commemorative Foundation, a nonprofit organization authorized by the United States Congress to establish a national commemorative work on federal land in Washington, D.C. to recognize the historic significance of the establishment of the Peace Corps in 1961 and to honor the timeless American ideals on which the Peace Corps was founded.

“The MPCE solicits all kinds of writing and artifacts that demonstrate the impact of Peace Corps service on both the volunteers and the communities they served,” said Demerly.

By formalizing this joint effort based on shared interests, both the MPCE and the PCCF have committed to telling the entirety of the Peace Corps story, ensuring that visitors understand the unique value of service both at home and abroad, the consequential achievements of Peace Corps volunteers and their host-country counterparts, and the timeless American ideals that motivate volunteer service.

“We imagine an experience wherein visitors explore interactive exhibits on peace education, foreign cultures, and the history of Peace Corps at the MPCE that fosters reflection and community. This agreement is an important step in realizing this vision together,” said Zack Klim, Director of the MPCE.

“Ed Demerly‘s writing is richly detailed and deeply felt,” said fellow retired HFC English instructor and author Dr. Rick Bailey. “It is a pleasure to travel back in time with him through his work.”

Meeting John Steinbeck en route to Peace Corps assignment

President John F. Kennedy’s establishment of the Peace Corps while Demerly was a student at Michigan State University inspired him to join after completing 2½ years in the U.S. Army. During his time in the military, he trained as an Airborne Ranger and served in the Army Medical Service Corps.

“Ed once told me that when he was en route to his Peace Corps assignment in the 1960s, he recognized the person on the flight to Southeast Asia; it was John Steinbeck. Steinbeck was flying to Vietnam to visit his son who was deployed there,” said HFC English instructor Dr. John Rietz.

Steinbeck won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature and the Pulitzer Prize. He wrote 33 books. His most notable include Of Mice and Men, The Grapes of Wrath, and East of Eden. Steinbeck died in 1968, not long after Demerly met him.

“In the early morning, the plane stopped for refueling in Guam. We were allowed to deplane for a stretch break. Most of us remained asleep, but I – always one for genuine adventure, one who couldn’t say I was in Guam unless my feet were on the ground in Guam – deplaned onto the tarmac with a few other volunteers,” recalled Demerly. “As we huddled together talking at 2:00 a.m., I noticed an older man smoking in the distance. I thought he looked a little like the photos I had seen of John Steinbeck, but how could that be? He wandered over to our group and asked where we were headed. We explained that we were Peace Corps volunteers headed to Malaysia. He was headed to Saigon for the holidays to meet his son, a captain in the army. He introduced himself, ‘I’m John Steinbeck, by the way.’ Wow! A college English major meets one of his author heroes! Steinbeck was in first class, so we were unaware that he was on the plane. He seemed older and smaller than I imagined. He wished us well.”

Hours later, their plane landed in Tan Son Nhut Airport in Saigon for another refueling.

“The landing was just as Elaine Steinbeck, who was accompanying her husband, later described in an interview with Steinbeck biographer Jay Parini: ‘It was a little nerve-wracking to land there. Instead of descending gradually, the plane had to bank steeply and dive to avoid sniper fire or rocket attacks,’” said Demerly. “The terminal was full of soldiers in fatigues. Those leaving looked exhausted, but relieved to be departing, while those arriving looked hesitant and wary. Our departure was also straight up, high enough to avoid ground fire before leveling off.”

Demerly asked to be assigned in a remote area

Demerly chronicles his two years in the Peace Corps with Living in the Ulu. Fortunately for him, the majority of this book was written more than 55 years ago. Demerly used the letters he wrote to his mother throughout his time in the Peace Corps. His mother kept them in chronological order, allowing him to adapt them for his memoir.

“Essentially, they’re verbatim. I took out some private things to my family that would’ve detracted from the book. It includes 70 photos. The beginning and ending are narrative,” he explained. “As I was reading through the letters, the memories came rushing back, especially those I’d forgotten about. That was such a great experience for me.”

During his time in the Peace Corps, Demerly taught all subjects at an Australian mission school called Holy Cross School in a small rainforest village called Kuala Sapi in North Borneo, Malaysia.

“My Peace Corps assignment was, by choice, in the Borneo ulu, which was a half day or more upriver into the equatorial rainforest in a small indigenous village without electricity, without telephones, without running water, without other White people, without roads,” recalled Demerly. “What I did find were snakes, bats, lizards, malaria-carrying mosquitoes, scorpions, and 3-4 months of unrelenting monsoon rains. The villagers and large families were very welcoming, supportive, hardworking people subsisting on meager rice paddies, fruit trees, gardens, and whatever the river and the rainforest could provide. When I was training for the Peace Corps, we were told we’d be assigned to places like that. I sought that because I wanted the real thing.”

Holy Cross was a primary school founded by Australian Anglican missionaries 10 years before Demerly’s arrival. In 1964, four years before Demerly’s arrival, this area of Borneo was still a part of the British Empire, but became a state in the Malaysian Federation. The school still functioned in English. When it was established, the school invited its first generation of students to learn to read and write. In those first years, children up to age 10 could enroll as kindergarteners.

“Some of my 6th-grade students were 16. Others were 11,” explained Demerly.

First generation who could read and write

Demerly received vaccinations prior to his Peace Corps assignment. He also took his anti-malaria pills and other preventive measures regularly. Other than food poisoning and a foot infection, he was fortunate enough to avoid the major ailments that might present hazards for visitors.

“Walking through water up to my knees during monsoon season to get to the school was more circumstantial than challenging,” he said. “Monsoon season lasted up to four months. You couldn’t dry your laundry because it was so humid. I never kept leather shoes because they would just mildew.”

Demerly was the only teacher with a college degree. Two other teachers had high school certificates, while the remaining four had completed 6th grade. Very rarely was the full staff of seven teachers present. For weeks at a time, they had as few as three teachers and no principal educating 140 students. National exams were a path for students to attend high schools, which were only in coastal cities. However, the limited space in these high schools led to limitations in the number of primary school students who could attend.

“The year prior to my arrival, four of 18 students from Kuala Sapi passed the 6th-grade exam,” said Demerly. “There were other limitations and obstacles in the way of our goal to achieve greater success on the national exam. Students were studying in a second language. Although they began learning English in kindergarten, they used English only in the classroom, not in their private lives. Textbooks, primarily only math textbooks, were old and had to be shared. In many ways, they seemed irrelevant to the students’ lives anyway, as they included examples of telephones, packaged food, movie theaters, apartment buildings, airports, refrigeration, taxis, and so on. The primary means of instruction was taking notes from the chalkboard. At times, attendance was irregular due to outbreaks of malaria and the monsoons. Girls sometimes left school in their early teens to get married.”

He continued: “The work I signed on to do was hard work. Fortunately, I loved my work. I was teaching in circumstances where we seldom had enough teachers. There were no supplies and very few books. A lot of it was creative teaching, but even that challenge I welcomed. This was the first generation of educated children in this village. Their parents couldn’t read or write, nor could they help them with homework. For the most part, the children were enthusiastic learners, and it was rewarding to see their growth.”

“Overwhelmingly wonderful”

Although his students were respectful and attentive, Demerly remembered a few memorable incidents that led to classroom interruptions. One day, the students grew restless, then suddenly rushed out of the classroom, as did students from the other classrooms.

“A small biplane was about to land on the river. A businessman from a distant lumber camp was arriving to speak to the village chief. That half-hour was well spent watching the landing from a distance,” said Demerly. “Another day, several girls sitting near the wall began to squirm in alarm. Soon, all the students shifted away from the wall and pointed, speaking excitedly in their native language. They had spotted an eight-inch poisonous centipede crawling on the wall. Not realizing that I, too, probably should have been cautious, I took some papers and brushed it out an open window. I had been teaching distance, time, and speed arithmetic problems, so our next chalkboard problem read: ‘If a centipede can crawl three feet per minute, how long would it take it to cross a classroom that is 21 feet long?’ It was my effort to teach in the moment.”

During monsoon season, a sudden gush of torrential rain swept into an open classroom, dousing students and their materials. Demerly and his class huddled in a far corner of the room for about 15 minutes, then started mopping up the classroom with small handmade whisk brooms.

Holy Cross was located on a space that had been part of a rubber tree plantation. A few of the rubber trees remained. During their seeding season, these trees would sometimes shoot their seeds into the air with an audible crack, followed by the seeds loudly rolling off the school’s steel roof.

“Just another interruption,” said Demerly. “I enjoyed every day on my job as a teacher to these students who were the first generation to be educated in that community. The whole village was very endearing to me as we grew to know each other. Just the experience of living in such a foreign culture where everything was new – the food, the languages, the housing, the weddings, the funerals, the parties, the wildlife, the farming, the elections, the sports, the weather, the holidays, the superstitions, the ‘grocery shopping,’ the currency, the history, etc. – all of it was overwhelmingly wonderful.”

He continued: “Near the year’s end, the students consented to attending afternoon classes in a final effort to pass the national exam. Practice tests looked promising. On the day of the test, I was not allowed near the school. They were on their own. Then we waited for more than six weeks for the results. To the great credit of my hardworking, hopeful students, eight of my 18 students passed – almost half the class, and twice as many as the previous year! And for the first time, three girls passed. A goal accomplished!”

Returning to Malaysia after four decades

Demerly returned to the Malaysian village in 2009 for the first time in more than 40 years, an event that is chronicled in the last several chapters of Living in the Ulu.

There is now a road through the rain forest that leads to the village. A former student transported Demerly to the village via car instead of boat. Even in 2009, the road was more of a logging trail.

Other changes were present, including electricity, a cell tower on the hilltop of the village, and internet access. This allows Demerly to keep in touch with them through social media.

“Times certainly have changed there,” he said, laughing. “I have not returned to Malaysia since 2009, but I have been able to correspond with former students, staff, and residents. And it has been a pleasure to be able to send them copies of my book.”

Peace Corps experience made him appreciate how fortunate Americans are

Demerly looks back fondly on his time in the Peace Corps. Most prominently, his experience opened his eyes to a world outside the U.S. and beyond that of a tourist.

“During my time in the ulu, I was the only White person for miles around. I came to identify so closely with my community that on one occasion when another White person arrived at the village and I noticed him from a distance, my thought was, ‘What is that foreign person doing here?’” recalled Demerly. “I’m sure that my experience helps me empathize in some ways with citizens of developing nations all over the world. Equally significant, my Peace Corps experience offered me a new appreciation of how fortunate we Americans are, not only economically, but also with the freedoms that most of us can’t begin to appreciate, our healthcare systems, our self-governance, and our access to education.”

By the same token, the U.S. could learn from other cultures, Demerly pointed out. Malaysia is a very diverse nation with great numbers of Malays, Chinese, Filipinos, Indians, Europeans, and numerous indigenous groups.

“They seem to work well together with a sense of unity,” said Demerly. “The Christian school where I taught remains very active. In its effort to unify the new nation, Malaysia established Malay as the universal language. Holy Cross hired qualified teachers from the Malay Peninsula. Today, the faculty is primarily Muslim teachers working in a Christian school. They have earned respect and admiration from the students and the community.”

Peace Corps training led to long teaching career at HFC

Born in Owosso just weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Demerly was the second of five children and the first in his family to attend college. He was the salutatorian of the class of 1959 at Perry High School.

He earned a full scholarship to MSU, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in English and his secondary education teaching credentials. During his time at MSU, he was required to take two years of Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) courses. He opted to continue in ROTC for two more years, earning a second lieutenant’s commission before enlisting in the Army.

After his service in the Army and the Peace Corps, Demerly earned his master’s degree in English at MSU through the G.I. Bill. He later earned his elementary school teaching certification from Eastern Michigan University. Demerly understands French, Malay, and Kadazan.

Demerly taught for 46 years, 10 in the Dearborn Public Schools. In 1979, he began teaching at HFC (then Henry Ford Community College), where he stayed for 36 years.

“Teaching English as a foreign language in Malaysia offered me the experience to become the founder of Dearborn’s ESL program in the 1970s,” he said.

The Michigan College English Association (MCEA) Executive Board nominated Demerly for the Standley Award.

“We can think of no one who has served the CEA and the profession of college English teaching, longer, better, or more faithfully than Ed. He joined the MCEA in 1982, and subsequently served as president for several years, program chair for several conferences, and Michigan’s CEA liaison for about 15 years. He remains an active Board member and a faithful MCEA conference participant, moderator, and helped in any way he could," the MCEA released in a statement.

Demerly was hired at HFC to teach ESL when then-ESL instructor Dr. Ellen Hoekstra was on leave. Initially, it was supposed to be a one-year assignment at the College. However, Hoekstra never returned, allowing Demerly to remain at HFC for the remainder of his career. One highlight of his time at HFC: With retired English instructor Dr. Mary Assel, Demerly founded the English Language Institute (ELI) in 2001. He retired in 2008 but remained at the College as a part-time instructor until retiring permanently in 2014.

"These honors, like the letters in his book, and his tenure here at the College, reveal a life of caring, compassionate service,” said HFC English instructor and Chair of the Faculty Senate Dr. Michael Hill. “Ed remains an inspiration for all faculty here at the College who want to the see the relevance of our work outside these walls.”

Added Rietz: “Ed is an unusually fine person: unassuming, kind, and respectful of everyone he encounters. He took a particular interest in our immigrant students and their acquisition of English, an interest that culminated in the formation of the ELI. It's easy to believe that his time in the Peace Corps influenced the work he took on when he joined our faculty at the College, and he left behind a very valuable legacy for Dearborn's immigrant population.”

Related content: Peace Corps informational video