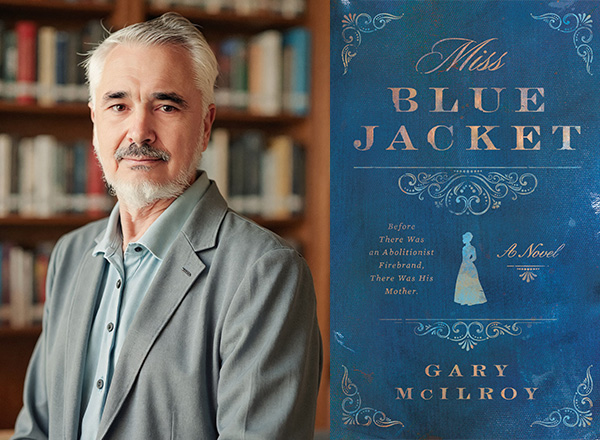

Retired English instructor authors book about famous abolitionist’s mother

When retired HFC English instructor Dr. Gary McIlroy wrote his latest book called Miss Blue Jacket – his first full-length novel – he decided to focus on Frances Lloyd Garrison (1776-1823) rather than her son, the renowned abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879).

“William Lloyd Garrison is rightly celebrated as one of the 19th century’s leading abolitionists,” said McIlroy. “Frances Maria Lloyd Garrison, his mother, is far less known. In fact, she wouldn’t be known today were it not for the fame of her son. Yet like many remarkable but largely anonymous women, her story deserves to be remembered and honored.”

Garrison wrote about Frances: “I had a mother once, who cared for me with such a passionate regard, who loved me so intensely, that no language can describe the yearnings of her soul – no instrument can measure the circumference of her maternal spirit. How often did she watch over me – weep over me – and pray over me! (I hope, not in vain.) She has been dead almost 11 years; but my grief at her loss is as poignant now as it was then… Rest in heaven, dear mother!”

A brief history of Frances Lloyd Garrison

McIlroy began researching Frances five years ago at the same time he was researching his nonfiction book, Turtles on a Black Gum Tree: The Life of Charles Ball.

“Most of what we know about her can be found in Henry Mayer’s rich and masterful biography of her son, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery,” he explained. “There, she emerges as an endearing and indomitable presence. Even so, much of her life – particularly her early years in New Brunswick – remains only faintly sketched, with many details lost to history.”

He continued: “There’s a fascinating debate about whether any historical work can be entirely nonfiction. As soon as you begin telling a story and bringing characters to life, imagining their inner worlds and emotional experiences, you’re entering the realm of fiction. In this instance, you couldn’t write a biography of Frances because of the dearth of factual detail.”

From New Brunswick to New England to Baltimore, Frances was forced to navigate a world torn apart by war, upended by trade disruptions, and burdened by disease and slavery. Sustained by her steadfast faith, Frances endured loss and separation. In doing so, she helped form the conscience of her surviving son, William, who would rise to become one of the fiercest voices in the American abolitionist movement.

“Frances was a towering figure of faith, strength, and good works. Her son absorbed her fervent religious convictions and transformed them into a righteous social calling that became his life’s mission,” explained McIlroy. “She was incredibly capable. She could butcher a moose, sail a skiff, bake bread, and help her mother keep up with the sewing demands of a large household. She also loved literature, wrote with graceful fluency, spoke French, and, as her son would later write, possessed a ‘vigorous, lustrous mind.’”

Her son was not just a vocal abolitionist, William was also a journalist, publisher, and social reformer. In 1831, he founded The Liberator, an anti-slavery newspaper published in Boston until 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery nationwide.

A staunch supporter of women’s rights in the 1870s, Garrison was a prominent voice for the women’s suffrage movement.

Abolitionist and author Frederick Douglass, who is often considered the most prominent leader of African American rights in the 19th century, gave Garrison’s eulogy upon his death in 1879. “In his death, we behold a great life ended, a great purchase achieved, a great career beautifully finished, and a great example of heroic endeavor nobly established. He moved not with the tide but against it. He rose not by the power of the Church or the State, but in bold, inflexible, and defiant opposition to the mighty power of both of them. It was the glory of this man that he could stand alone with the truth and calmly await the result.”

“A tribute to the women who shape great men, even when history forgets their names”

McIlroy explained the significance of the novel’s title, Miss Blue Jacket.

“The title comes from an anecdote her son told about how his parents met: ‘At the close of the evening prayer service, my father (Abijah Garrison) boldly asked leave to accompany my mother home, accosting her, for want of her real name, as ‘Miss Blue Jacket,’” said McIlroy.

Writing historical fiction and nonfiction can share more similarities than we realize.

“Both require rigorous research, thoughtful curation of facts, consistency, and a clear narrative perspective,” said McIlroy. “Ultimately, whether the story is imagined or factual, the writer’s goal is the same: To craft prose that is both clear and engaging, bringing the subject to life on the page.”

He spoke about the challenges of writing Miss Blue Jacket.

“It was difficult trying to portray the full humanity of a young woman born in 1776,” he said. “Still, I enjoyed the challenge of bringing a character to life.”

“In Miss Blue Jacket, the forgotten story of Frances Lloyd Garrison emerges from the shadows of history,” said independent book reviewer Mary Reynolds. “This powerful historical novel is a tribute to the women who shape great men, even when history forgets their names.”

Writing novels in retirement after 35 years at HFC

The middle of three sons, McIlroy was born in Detroit. He has been married to Monica Dewey since 1985. The couple, who has three children, reside in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

A graduate of Lakeview High School in St. Clair Shores, McIlroy earned his bachelor’s degree in English and political science from Oakland University. A two-time alumnus of the University of Detroit Mercy (then the University of Detroit), he earned both his master’s and doctoral degrees in American literature.

For more than 40 years, McIlroy taught writing and literature at the college level. He taught at UDM and Marygrove College before coming to HFC (then Henry Ford Community College) in 1985. He retired in 2020.

McIlroy has penned three books. His early academic writing focused primarily on the Transcendental era with a strong interest in nature writers. His essays on authors Henry David Thoreau and Annie Dillard have appeared in the South Atlantic Quarterly, American Literature, Thoreau Quarterly, and in the anthologies Earthly Words and Contemporary American Writers.

He is hard at work on his next book, which will be published in 2026.

“I’m currently writing a novel about an English graduate student in the 1970s and early 1980s and his early career as a professor,” he said. “It loosely follows the chronology of my own graduate education and early teaching experiences, but it is not strictly autobiographical. Still, it reflects the state of the field at the time and the dramatic changes it was undergoing. My professors had once been assured that there would not be enough English Ph.D.s to meet the needs of California. By the time I graduated, the job market had already tightened, to say the least! Closely related was the emergence of departments and fields of study focusing on the teaching of writing, which used to be within the purview of traditional departments of English.”