Photo: HFC alumnus and award-winning actor Tom Skerritt, third from left, in the 1979 movie Alien.

With more than 200 TV and movie credits to his name and a career spanning more than 55 years, award-winning actor/director Tom Skerritt has been a constant presence on the big and small screens.

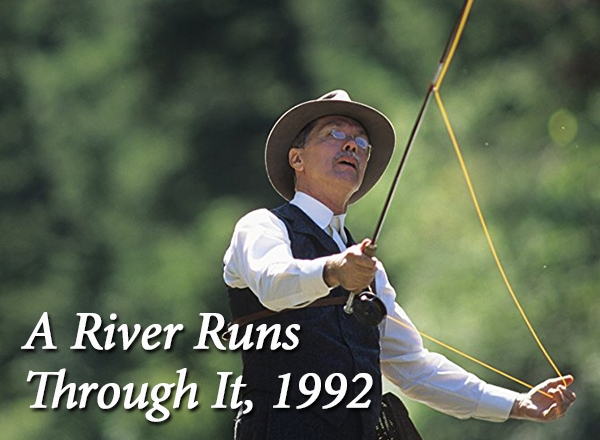

Skerritt has appeared in many iconic movies, including 1970’s MASH, 1971’s Harold and Maude, 1979’s Alien, 1983’s The Dead Zone, 1986’s Top Gun, 1989’s Steel Magnolias, 1992’s A River Runs Through It, 1997’s Contact, 2012’s Ted, among many others.

He won an Emmy and was nominated for two Golden Globes for his portrayal of Sheriff Jimmy Brock on the drama Picket Fences (he also directed three episodes). He’s had prominent recurring roles on Brothers & Sisters and Cheers.

He’s made numerous guest appearances on the TV shows The Virginian, Twelve O’Clock High, Bonanza, The Fugitive, Gunsmoke, Kolchak: The Night Stalker, Chicago Hope, Will & Grace, The West Wing, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, Leverage, The Closer, White Collar, The Good Wife, and Madam Secretary.

He’s worked alongside many movie greats, among them Robert Redford, Sydney Pollack, Donald Sutherland, Robert Duvall, Elliott Gould, Sigourney Weaver, Christopher Walken, Tom Cruise, Julia Roberts, Sally Field, Shirley MacLaine, Diane Keaton, Clint Eastwood, Brad Pitt, Jodie Foster, Matthew McConaughey, Bruce Willis, Jessica Lange, Joan Allen, and Kathy Bates.

And he got his start at Henry Ford College.

Skerritt in A River Runs Through It, 1992

Skerritt in Contact, 1997

Skerritt in Steel Magnolias, 1989

Skerritt in TV's Picket Fences

“I am what Michigan gave me, and I’m very fortunate for it. It gave me a place to begin. To define these things, they’re undefinable,” said Skerritt. “It was a good, solid experience I had in Detroit. I knew the community there and it had a work ethic that I aspired to. Midwestern effort – I picked that up there and that’s what I carry with me all the time.”

A kick in the pants gets the dream started

Born in Detroit in 1933, Skerritt is the youngest of four siblings. He went to the now-closed MacKenzie High School in Detroit, where he played football. He later joined the U.S. Air Force.

“I wasn’t born into scholarship,” said Skerritt, who lives in Seattle. “(MacKenzie) was designed for 2,000 students and had 4,000 students, so it was just ‘get ‘em in and push ‘em out.’ I never took school seriously. Knowing that I needed to get an education, I had to knuckle down. The military gave me some sense of responsibility in terms of how I pursue my life and how I’m responsible for it.”

Skerritt served in the Air Force for four years during the Korean War. After leaving the military, he enrolled at HFC in 1956, taking general studies and English classes (His late brother James taught English at HFC. “He was a really good man,” Skerritt said of James).

“I was grateful to have been out of the service and to have the G.I. Bill pay for me to go to college. (HFC) was convenient for me. I don’t think I even had an automobile at the time. It was a challenge, and it was enjoyable. I was just grateful to be able to go to college. (HFC) made it easier to prepare for a larger college like Wayne State University.”

Skerritt transferred to Wayne State and later attended the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), hoping to become a film director. He left UCLA a semester shy of graduation to make his acting debut in 1962’s War Hunt, alongside Redford and Pollack.

Oddly enough, Skerritt never intended to become an actor. He wanted to be a screenwriter and director.

“I was at UCLA as an English major when I saw (1941’s) Citizen Kane,” said Skerritt. “I thought, ‘Wow, I want to do that. I want to write and direct at that level’ – which is a great level to go for.”

He realized in order to direct actors and to write for actors, he had to learn how to be an actor himself. So he began doing theater and was first noticed in a UCLA production of N. Richard Nash’s The Rainmaker. This led to War Hunt, which was also Pollack’s film debut and Redford’s second film.

“I thought this was a great way of learning what this whole thing is about (filmmaking) by being on a set,” he said. “(Redford and Pollack) became very good actors; they were teaching me quite a bit.”

While filming War Hunt, he also met writer/director Robert Altman, and they became fast friends.

Skerritt in MASH, 1970

“I didn’t know anything about directing but here’s a guy who’s answering my questions and giving me information. He’s mentoring me. Several years later, he called me one day and said, ‘I’m directing a movie and want you to be in it. It’s called MASH,’” recalled Skerritt. “Directors rarely ever direct, with some exceptions. They just say, ‘That’s not gonna work’ or ‘Hey, that’s not a bad idea. Let’s do that.’ But good filmmakers direct, and I’ve worked with some of the best.”

Robert Redford, and a place for promising young filmmakers

Throughout the years, Skerritt stayed in touch with Redford, best known for films like 1973’s The Sting and 1976’s All the President’s Men. According to Skerritt, he and Redford look at the film industry the same way – with a jaundiced eye.

“We never fully trusted the studio approach to things. The problem was the exclusion of young, promising, independent filmmakers. We used to talk about that a lot in the 1960s. How do you find these young filmmakers? How you support them? How you develop them? Hollywood was not the place to do that. You have to come in as a recognized entity to break into the business in Hollywood,” explained Skerritt.

“From those conversations, Redford one day told me he bought some property in Provo, UT. He said, ‘I’d love to be able to build a school here for independent filmmakers, so they can have a place to come to, apart from L.A., to learn the trade and make inexpensive short films.’ He’s always had a broad view of the business and a responsibility to other filmmakers,” said Skerritt.

Redford’s dream became the Sundance Institute, a non-profit organization committed to the growth of independent filmmakers. One of Sundance’s programs is the Sundance Film Festival, a critically acclaimed annual film festival serving as a platform for independent filmmakers.

Skerritt took a page from his old friend and in 2002 founded The Film School in Seattle, a program that also helps independent filmmakers. Skerritt pointed out its focus is on the craft of storytelling.

The Film School attracts students from all over the world, given Seattle’s thriving creative culture and booming independent film community. It’s elevated the art of storytelling by training a new generation of screenwriters and filmmakers. Many graduates have gone on to success, starting film companies, making movies, and signing with agents.

The magic is always in the story

“Story has been the only thing that makes sense in this business,” said Skerritt. “It seems to be absent in a lot of Hollywood films – the big productions – over a period of years. Seattle is one of the most literate cities in the country. We’ve got all these great and wonderful writers here. We have a sense of storytelling here. We have an enthusiastic film community here that was at a loss as to how to make independent films. The Film School has been going on 16 years and was designed to bring in young people to learn how to tell stories. And they’ve found themselves in a way they otherwise wouldn’t. Many alumni come out of it saying, ‘It’s been life-changing.’”

In 2012, Skerritt and Evan Bailey, a former U.S. Army captain, founded the Red Badge Project. Its mission is to support wounded veterans in their journey to reconstruct their individual sense of purpose, understanding of self-worth, and their place in the community as they discover and give voice to their unique stories.

“This self-realization we’ve had from alumni, we’ve taken to (the vets). So now we’re in several different VA centers teaching storytelling, which is really self-realization,” said Skerritt. “That exercise of finding out something about yourself that you’d never otherwise know unless you wrote it… not about how you got PTSD, but how to utilize that PTSD condition to drive your instincts and impulses. You don’t even have to show it to anybody. That’s the basis of it, and it’s been very successful. Storytelling – being able to express yourself in words – is a very significant way of channeling all this pain and energy in a positive way. The one thing about writing is it’s yours and yours alone.”

For Skerritt, it’s never been about acting. It’s been about storytelling.

“Always has been,” he said. “Good writing will always make anything work. The better you tell the story, the better everyone is moved by it. If you have a solid script, everyone’s inspired by it and it just elevates performances. That’s no secret. Good storytelling is what everybody responds to: writers, producers, actors, directors, and — ultimately — the audience because you’re respecting their intelligence.”

Visit www.thefilmschool.com and www.theredbadgeproject.com.